Women's Fashion in Mid 1500s Germany

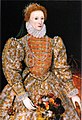

English language opulence, Italian reticella lace ruff, (possibly) Polish ornamentation, a French farthingale, and Castilian severity: The "Ermine Portrait" of Elizabeth I

Fashion in the period 1550–1600 in Western European clothing was characterized past increased opulence. Contrasting fabrics, slashes, embroidery, applied trims, and other forms of surface ornamentation remained prominent. The broad silhouette, conical for women with breadth at the hips and broadly square for men with width at the shoulders had reached its peak in the 1530s, and past mid-century a tall, narrow line with a V-lined waist was dorsum in fashion. Sleeves and women's skirts then began to widen over again, with emphasis at the shoulder that would proceed into the side by side century. The characteristic garment of the period was the ruff, which began as a modest ruffle attached to the neckband of a shirt or smock and grew into a separate garment of fine linen, trimmed with lace, cutwork or embroidery, and shaped into crisp, precise folds with starch and heated irons.

General trends [edit]

Isaac Oliver's allegorical painting of 1590–95 contrasts virtuous and licentious dress and beliefs.

Spanish style [edit]

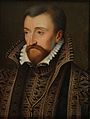

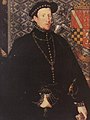

Charles V, rex of Kingdom of spain, Naples, and Sicily and Holy Roman Emperor, handed over the kingdom of Spain to his son Philip Ii and the Empire to his brother Ferdinand I in 1558, ending the domination of western Europe by a single court, but the Spanish taste for sombre richness of dress would dominate mode for the remainder of the century.[i] [2] New alliances and trading patterns arose equally the split betwixt Catholic and Protestant countries became more pronounced. The severe, rigid fashions of the Castilian court were dominant everywhere except French republic and Italy. Blackness garments were worn for the near formal occasions. Black was hard and expensive to dye, and seen as luxurious, if in an austere manner. As well equally Spanish courtiers, information technology appealed to wealthy middle-class Protestants. Regional styles were withal distinct. The clothing was very intricate, elaborate and fabricated with heavy fabrics such every bit velvet and raised silk, topped off with brightly coloured jewellery such as rubies, diamonds and pearls to contrast the black backdrop of the clothing.[3] Janet Arnold in her analysis of Queen Elizabeth's wardrobe records identifies French, Italian, Dutch, and Polish styles for bodices and sleeves, as well as Castilian.[iv]

Italian doublet and hose busy with practical trim and parallel cuts contrast with a severe black jerkin, 1560.

Linen ruffs grew from a narrow frill at neck and wrists to a broad "cartwheel" style that required a wire support by the 1580s. Ruffs were worn throughout Europe, by men and women of all classes, and were made of rectangular lengths of linen as long as nineteen yards.[5] Later ruffs were fabricated of delicate reticella, a cutwork lace that evolved into the needlelaces of the 17th century.[6]

Elizabethan Manner [edit]

Since Elizabeth I, Queen of England, was the ruler, women's fashion became i of the almost important aspects of this menstruum. As the Queen was always required to have a pure epitome, and although women's style became increasingly seductive, the idea of the perfect Elizabethan women was never forgotten.[7]

The Elizabethan era had its ain customs and social rules that were reflected in their fashion. Style would depend usually of social status and Elizabethans were bound to obey The Elizabethan Sumptuary Laws, which oversaw the style and materials worn.[8]

Elizabethan sumptuary laws were used to control behaviour and to ensure that a specific social structure was maintained. These rules were well known by all the English language people and penalties for violating these sumptuary laws included harsh fines. Most of the time they ended in the loss of belongings, title and even life.[ix]

Regarding fabrics and materials for the clothes construction, only royalty was permitted to clothing ermine. Other nobles (bottom ones) were allowed only to wear foxes and otters. Clothes worn during this era were mostly inspired by geometric shapes, probably derived from the high interest in science and mathematics from that era.[10] "Padding and quilting together with the use of whalebone or buckram for stiffening purposes were used to gain geometric effect with emphasis on giving the illusion of a small-scale waist".[seven]

The upper classes, besides, were restricted. Certain materials such equally cloth of gold could merely exist worn past the Queen, her mother, children, aunts, and sisters, as well as duchesses, marchionesses, and countesses. Viscountesses and baronesses, among others, withal, were non allowed to wear this fabric.[11]

Not only fabrics were restricted on the Elizabethan era, but also colours, depending on social status. Royal was merely allowed to be worn past the Queen and her directly family members. Depending on social status, the colour could be used in any clothing or would be limited to mantles, doublets, jerkins, or other specific items.[12] Lower classes were only allowed to use brown, beige, yellowish, orange, green, gray and bluish in wool, linen and sheepskin, while usual fabrics for upper class were silk or velvet.[13]

Fabrics and trims [edit]

The full general trend towards abundant surface ornamentation in the Elizabethan Era was expressed in wearable, specially amongst the aristocracy in England. Shirts and chemises were embroidered with blackwork and edged in lace. Heavy cut velvets and brocades were further ornamented with applied bobbin lace, gold and silver embroidery, and jewels.[14] Toward the end of the period, polychrome (multicoloured) silk embroidery became highly desirable and fashionable for the public representation of aristocratic wealth.[15] [xvi]

The origins of the trend for sombre colours are elusive, just are generally attributed to the growing influence of Spain and possibly the importation of Spanish merino wools. The Depression Countries, High german states, Scandinavia, England, French republic, and Italy all absorbed the sobering and formal influence of Spanish apparel after the mid-1520s. Fine textiles could be dyed "in the grain" (with the expensive kermes), alone or every bit an over-dye with woad, to produce a broad range of colours from blacks and greys through browns, murreys, purples, and sanguines.[17] [eighteen] Cheap reds, oranges and pinks were dyed with madder and blues with woad, while a variety of common plants produced xanthous dyes, although near were prone to fading.

By the stop of the period, there was a sharp distinction between the sober fashions favoured by Protestants in England and the Netherlands, which nonetheless showed heavy Castilian influence, and the lite, revealing fashions of the French and Italian courts. This distinction would carry over well into the seventeenth century.

Women's fashion [edit]

Spanish manner: Elizabeth of Valois, Queen of Spain, wears a black gown with flooring-length sleeves lined in white, with the cone-shaped skirts created past the Spanish farthingale, 1565.

Elizabeth I wears padded shoulder rolls and an embroidered partlet and sleeves. Her low-necked chemise is just visible above the arched bodice, 1572.

Women's outer vesture more often than not consisted of a loose or fitted gown worn over a kirtle or petticoat (or both). An alternative to the gown was a short jacket or a doublet cut with a loftier neckline. The narrow-shouldered, wide-cuffed "trumpet" sleeves characteristic of the 1540s and 1550s in France and England disappeared in the 1560s, in favor of French and Spanish styles with narrower sleeves. Overall, the silhouette was narrow through the 1560s and gradually widened, with accent at the shoulder and hip. The slashing technique, seen in Italian dress in the 1560s, evolved into single or double rows of loops at the shoulder with contrasting linings. By the 1580s these had been adapted in England as padded and jeweled shoulder rolls.[4] [xiv] [19] [20] [21]

Gown, kirtle, and petticoat [edit]

The common upper garment was a gown, called in Spanish ropa, in French robe, and in English language either gown or frock. Gowns were made in a diverseness of styles: Loose or fitted (called in England a French gown); with brusque one-half sleeves or long sleeves; and floor length (a round gowns) or with a trailing train (clothing).[20] [21]

The gown was worn over a kirtle or petticoat (or both, for warmth). Prior to 1545, the kirtle consisted of a fitted one-piece garment.[22] Later that date, either kirtles or petticoats might have attached bodices or bodies that fastened with lacing or hooks and eyes and almost had sleeves that were pinned or laced in place. The parts of the kirtle or petticoat that showed beneath the gown were usually fabricated of richer fabrics, particularly the front end panel forepart of the skirts.[twenty] [21]

The bodices of French, Spanish, and English language styles were stiffened into a cone or flattened, triangular shape catastrophe in a V at the forepart of the woman's waist. Italian mode uniquely featured a wide U-shape rather than a Five.[14] Spanish women likewise wore boned, heavy corsets known as "Spanish bodies" that compressed the trunk into a smaller simply equally geometric cone.[23] Bodices could be loftier-necked or have a broad, depression, square neckline, oft with a slight arch at the forepart early in the period. They attached with hooks in front or were laced at the side-back seam. High-necked bodices styled similar men's doublets might spike with hooks or buttons. Italian and German way retained the front-laced bodice of the previous menstruum, with the ties laced in parallel rows.

Underwear [edit]

Elizabeth Vernon at her dressing tabular array wears an embroidered linen jacket over her rose-pink corset, 1590s.

During this period, women's underwear consisted of a washable linen chemise or smock. This was the only commodity of vesture that was worn by every woman, regardless of class. Wealthy women'due south smocks were embroidered and trimmed with narrow lace. Smocks were made of rectangular lengths of linen; in northern Europe the smock skimmed the trunk and was widened with triangular gores, while in Mediterranean countries smocks were cut fuller in the torso and sleeves. High-necked smocks were worn under high-necked fashions, to protect the expensive outer garments from body oils and dirt. There is pictorial evidence that Venetian courtesans wore linen or silk drawers, but no show that drawers were worn in England.[twenty] [24]

Stockings or hose were generally fabricated of woven wool sewn to shape and held in place with ribbon garters.

The first corsets likely originated in sixteenth-century Espana from bodice-like garments that were made with thick fabrics. The fashion spread from there to Italy, and and then to France and (eventually) England, where it was chosen a pair of bodies, being made in two parts which laced dorsum and front end. The corset was restricted to aristocratic fashion, and was a fitted bodice stiffened with reeds called bents, woods, or whalebone.[20] [25]

Skirts were held in the proper shape by a farthingale or hoop skirt. In Kingdom of spain, the cone-shaped Spanish farthingale remained in fashion into the early 17th century. Information technology was only briefly stylish in French republic, where a padded roll or French farthingale (called in England a bum roll) held the skirts out in a rounded shape at the waist, falling in soft folds to the floor. In England, the Spanish farthingale was worn through the 1570s, and was gradually replaced past the French farthingale. By the 1590s, skirts were pinned to wide wheel farthingales to accomplish a drum shape.[14] [21] [26]

Partlet [edit]

A low neckline might exist filled with an infill (called in English a partlet). Partlets worn over the smock simply nether the kirtle and gown were typically made of lawn (a fine linen). Partlets were also worn over the kirtle and gown. The colours of "over-partlets" varied, merely white and blackness were the almost common. The partlet might be fabricated of the same fabric every bit the kirtle and richly decorated with lace detailing to complement information technology.[27] Embroidered partlet and sleeve sets were frequently given to Elizabeth as New year's day's gifts.

Outerwear [edit]

Women wore sturdy overskirts chosen safeguards over their dresses for riding or travel on dirty roads. Hooded cloaks were worn overall in bad weather. One description mentions strings being attached to the stirrup or foot to concord the skirts in place when riding. Mantles were also popular and described as modern day bench warmers: a square blanket or carpet that is attached to the shoulder, worn around the trunk, or on the knees for extra warmth.[28] [29]

Besides keeping warm, Elizabethans cloaks were useful for whatsoever type of weather condition; the Cassock, commonly known as the Dutch cloak, was another kind of cloak. Its proper noun implies some military ideals and has been used since the showtime of the 16th century and therefore has many forms. The cloak is identified past its flaring out at the shoulders and the intricacy of decoration. The cloak was worn to the ankle, waist or fork. Information technology too had specific measurements of 3/4 cut. The longer lengths were more pop for travel and came with many variations. These include: taller collars than normal, upturned collar or no collar at all and sleeves. The French cloak was quite the opposite of the Dutch and was worn anywhere from the knees to the talocrural joint. It was typically worn over the left shoulder and included a cape that came to the elbow. It was a highly decorated cloak. The Castilian cloak or cape was well known to be stiff, have a very busy hood and was worn to the hip or waist. The over-gown for women was very plain and worn loosely to the floor or talocrural joint length. The Juppe had a relation to the safeguard and they would ordinarily exist worn together. The Juppe replaced the Dutch Cloak and was most probable a loose form of the doublet.[28] [30] [31]

Accessories [edit]

The fashion for wearing or carrying the pelt of a sable or marten spread from continental Europe into England in this period; costume historians call these accessories zibellini or "flea furs". The near expensive zibellini had faces and paws of goldsmith's work with jewelled optics. Queen Elizabeth received 1 as a New Years gift in 1584.[32] Gloves of perfumed leather featured embroidered cuffs. Folding fans appeared late in the period, replacing flat fans of ostrich feathers.[4]

Jewelry was also pop among those that could afford it. Necklaces were beaded gold or silvery bondage and worn in concentric circles reaching as far down equally the waist. Ruffs also had a jewelry attachment such every bit glass beads, embroidery, gems, brooches or flowers. The jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots are well-documented. Belts were a surprising necessity: used either for fashion or more practical purposes. Lower classes wore them nearly as tool belts with the upper classes using them as another place to add jewels and gems alike. Scarves, although not often mentioned, had a significant impact on the Elizabethan style past existence a multipurpose piece of clothing. They could be worn on the head to protect desirable stake pare from the sun, warm the cervix on a colder day, and accentuate the colour scheme of a gown or whole outfit. The upper class had silken scarves of every color to brighten up an outfit with the golden thread and tassels hanging off of information technology.

While travelling, noblewomen would wear oval masks of black velvet called visards to protect their faces from the sun.

Curled hair, twisted and pinned upwardly

Hairstyles and headgear [edit]

Married and grown women covered their hair, equally they had in previous periods.[33] Early on in the flow, hair was parted in the center and fluffed over the temples. Later, front hair was curled and puffed high over the brow. Wigs and false hairpieces were used to extend the pilus.

In a typical hairstyle of the menstruum, front pilus is curled and back pilus is worn long, twisted and wound with ribbons and so coiled and pinned up.

A close-fitting linen cap chosen a coif or biggins was worn, alone or nether other hats or hoods, especially in holland and England. Many embroidered and bobbin-lace-trimmed English language coifs survive from this menstruation.[sixteen] The French hood was worn throughout the period in both France and England. Another fashionable headdress was a caul, or cap, of cyberspace-work lined in silk attached to a ring, which covered the pinned up pilus. This style of headdress had also been seen in Germany in the first half of the century.[34] Widows in mourning wore black hoods with sheer black veils.

Makeup [edit]

The ideal standard of beauty for women in the Elizabethan era was to take lite or naturally cherry hair, a pale complexion, and reddish cheeks and lips, drawing on the mode of Queen Elizabeth. The goal was to await very "English," since the primary enemy of England was Spain, and in Kingdom of spain darker hair was ascendant.[35] [36]

To further lighten their complexion, women wore white make-upward on their faces. This make-upwardly, called Ceruse, was fabricated upwards of white pb and vinegar. While this makeup was constructive, the white lead made it poisonous. Women in this fourth dimension oftentimes contracted lead poisoning, resulting in expiry before the age of 50. Other ingredients used equally make-upward were sulfur, alum, and tin ash. In addition to using make-upwards to achieve a pale complexion, women in this era were bled to take the color out of their faces.[35] [36]

Cochineal, madder, and vermilion were used as dyes to achieve the bright red effects on the cheeks and lips. Kohl was used to darken the eyelashes and enhance the size and appearance of the eyes. [36]

Style gallery 1550s [edit]

-

one – 1550–55

-

2 – 1554

-

3 – 1554

-

4 – 1554

-

5 – 1555

-

6 – c. 1555

-

seven – 1557

-

8 – 1557

-

9 - 1557

-

x – 1555–58

- Florentine manner of the early 1550s features a loose gown of light-weight silk over a bodice and skirt (or kirtle) and an open up-necked partlet.

- Dutch style of 1554: A black gown with high puffed upper sleeves is worn over a black bodice and a greyness skirt with black trim. The loftier-necked chemise or partlet is worn open with the 3 pairs of ties that fasten it dangling gratuitous.

- Dutch fashion of 1554: High-necked gown, in Castilian style, trimmed with ruched white silk braid held in place with gilt buttons. With ample embroidered sleeves. Hair is covered with a French hood, instead of the traditional white coif, ornamented with pearls.

- Mary I wears a cloth-of-gold gown with fur-lined "trumpet" sleeves and a matching overpartlet with a flared collar, probably her coronation robes,[ citation needed ] 1554. Neither the sleeves nor the overpartlet would survive as fashionable items in England into the 1560s.

- Titian's Lady in White wears Venetian manner of 1555. The front-lacing bodice remained fashionable in Italian republic and the German States.

- Catherine de' Medici in a apparel with a high-arched bodice fur-lined "trumpet" sleeves, over a pinkish front end and matching paned undersleeves, c. 1555.

- An unknown adult female wears a nighttime gown trimmed or lined in fur over fitted undersleeves. A chain is knotted at her cervix. England, 1557.

- Bianca Ponzoni Anguissola wears a gold-colored gown with tied-on sleeves and a chemise with a wide band of gold embroidery at the neckline. She holds a jewelled fur or zibellino suspended from her waist by a aureate chain, Lombardy (Northern Italy), 1557.

- Mary Howard, Duchess of Norfolk wears a cloth-of-red velvet gown with "trumpet" sleeves and a gold neckline with a gilded embroidered overpartlet, 1557.

- The widowed Mary Nevill, Baroness Dacre wears a black gown (probably velvet) over black satin sleeves. Her neckband lining and chemise are embroidered with blackwork, and she wears a black hood and a fur tippet over her shoulders, afterwards 1550s.[37]

Mode gallery 1560s [edit]

-

one – 1560

-

2 – 1562

-

3 – 1563

-

4 – 1560s

-

5 – 1560–65

-

6 - 1560–65

-

7 – 1560s

-

8 – 1564

-

nine – 1564

- Eleanor of Toledo wears a black loose gown over a bodice and a sheer linen partlet. Her brown gloves have tan cuffs, 1560.

- Margaret Audley, Duchess of Norfolk wears the high-collared gown of the 1560s with puffed hanging sleeves. Nether it she wears a loftier-necked bodice and tight undersleeves and a petticoat with an elaborately embroidered forepart, 1562.

- The Gripsholm Portrait, thought to exist Elizabeth I, shows her wearing a red gown with a fur lining. She wears a red apartment hat over a minor cap or caul that confines her pilus.

- Mary Queen of Scots wears an open up French collar with an fastened ruff under a black gown with a flared neckband and white lining. Her blackness hat with a feather is decorated with pearls and worn over a caul that covers her hair, 1560s.

- Unknown lady property a pomander wears a blackness gown with puffed upper sleeves over a striped loftier-necked bodice or doublet. She wears a whitework cap below a sheer veil, 1560–65.

- Isabella de' Medici'due south bodice fastens with pocket-size golden buttons and loops. A double row of loops trims the shoulder, 1560–65.

- Isabel de Valois, Queen of Spain in severe Spanish fashion of the 1560s. Her loftier-necked black gown with split hanging sleeves is trimmed in bows with single loops and metallic tags or aiglets, and she carries a jewelled flea-fur on a chain.

- Portrait of Elsbeth Lochmann in modest German language style: she wears a light-colored petticoat trimmed with a broad ring of nighttime fabric at the hem, with a brown bodice and sleeves and an frock. An elaborate purse hangs from her belt, and she wears a linen headdress with a sheer veil, 1564.

- Sisters Ermengard and Walburg von Rietberg wears German front end-laced gowns of cerise satin trimmed with blackness bands of textile. They wear loftier-necked blackness over-partlets with bands of gilded trim and linen aprons. Their hair is tucked into jewelled cauls, 1564.

Style gallery 1570s [edit]

-

1 – 1570

-

2 - 1571

-

three – 1571

-

4 – 1571

-

5 – c. 1572

-

half-dozen – c. 1575

-

7 – c. 1578

-

viii – 1578

-

9 – 1579

- Horizontal lacing over a stomacher and an open chemise are characteristic of Venetian manner. The skirt is gathered at the waist.

- Consort of Spain, Anna of Austria by Alonso Sánchez Coello wearing Castilian fashion, 1571.

- Leonora di Toledo of Florence, Italy wears a blue gown with a flared collar and tight undersleeves with horizontal trim. The uncorseted Due south-shaped figure is clearly shown, 1571.

- Elizabeth of Republic of austria is portrayed past the French courtroom painter François Clouet in a brocade gown and a partlet with a lattice of jewels, 1571. The lattice partlet is a mutual French fashion.

- In this allegorical painting c. 1572, Elizabeth I wears a fitted gown with hanging sleeves over a matching arched bodice and skirt or petticoat, elaborate undersleeves, and a high-necked chemise with a ruff. Her skirt fits smoothly over a Spanish farthingale.

- Elizabeth I wears a doublet with fringed braid trim that forms button loops and a matching petticoat. Janet Arnold suggests that this method of trimming may be a Shine fashion (similar trimmings à la hussar were worn in the 19th century).

- Mary, Queen of Scots in captivity wears French fashions: her open ruff fastens at the base of the neck, and her skirt hangs in soft folds over a French farthingale. She wears a cap and veil.

- Nicholas Hilliard's miniature of his wife Alice shows her wearing an open partlet and a closed ruff. Her blackwork sleeves have a sheer overlayer. She wears a black hood with a veil, 1578.

- German style: Margarethe Elisabeth von Ansbach-Bayreuth wears a tall-collared black gown over a cherry-pink doublet with tight sleeves and a matching petticoat. She wears a black hat.

Style gallery 1580s [edit]

-

ane – 1580s

-

2 – 1580s

-

3 – 1580s

-

4 – 1582

-

5 – c. 1584

-

six – 1585–90

-

7 – 1585–90

-

8 – 1585

-

9 – 1589

- Lettice Knollys wears an embroidered black high-necked bodice with circular sleeves and skirt over a gilded petticoat or forepart and matching undersleeves, a lace cartwheel ruff and lace cuffs, and a alpine black hat with a jeweled ostrich plume, c. 1580s.

- Elizabeth I wears a black gown with vertical bands of trim on the bodice. The curved waistline and dropped front opening of the overskirt suggest that she is wearing a French roll to support her skirt. She wears a heart-shaped cap and a sheer veil busy with a pattern of pearls, early on 1580s.

- Ladies of the French courtroom c. 1580 wear gowns with broad French farthingales, long pointed bodices with revers and open up ruffs, and full sleeves. This style appears in England around 1590. Note the fashionable sway-backed posture that goes with the long bodice resting on the farthingale.

- Anne Knollys wears a blackness gown and full white sleeves trimmed with gold lace or braid. She wears a French hood with a jewelled biliment and a black veil, 1582.

- The Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Kingdom of spain is seen hither again wearing a Spanish farthingale, a airtight overskirt, and the typically Castilian, long, pointed oversleeves. She is wearing black, a attestation to the austere side of the Spanish court, c. 1584.

- Nicholas Hilliard'southward Unknown Adult female wears a cutwork cartwheel ruff. Her stomacher and wired heart-shaped coif are both decorated with blackwork embroidery, 1585–90.

- Elizabeth I wears a cartwheel ruff slightly open at the front, supported by a supportasse. Her blackwork sleeves accept sheer linen oversleeves, and she wears wired veil with bands of gold lace, 1585–ninety.

- Infanta Catalina Micaela of Spain wears an entirely black gown with lace collar and cuffs, with white inner sleeves trimmed with gilt embroidery or applied complect. Her jewellery includes a double string of pearls, a necklace, worked golden buttons and a chugalug.

- Elizabeth Brydges, aged 14, wears a black brocade gown over a French farthingale. The blackwork embroidery on her smock is visible above the arch of her bodice; her cuffs are also trimmed with blackwork. This style is uniquely English. She wears an open-fronted cartwheel ruff.

Style gallery 1590s [edit]

-

1 – 1592

-

two – 1592

-

iii – 1592

-

4 – c. 1592

-

v – 1593–95

-

half dozen – 1594

-

7 – 1590s

-

eight – c. 1595

- The widowed Bess of Hardwick, Countess of Shrewsbury, wears a black gown and cap with a linen ruff, 1590.

- Elizabeth I, 1592, wears a dark red gown (the textile is merely visible at the waist under her arms) with hanging sleeves lined in white satin to match her bodice, undersleeves, and petticoat, which is pinned to a cartwheel farthingale. She carries leather gloves and an early folding fan.

- Elizabeth I wears a painted petticoat with her black gown and cartwheel farthingale. She wears an open lace ruff and a sheer, wired veil frames her head and shoulders. Her skirt is ankle-length and shows her shoes, 1592.

- English adult female wears a fashion seen in many formal portraits of Puritan women in the 1590s, characterized by a black gown worn with a blackwork stomacher and a small French farthingale or half-whorl, with a fine linen ruff and moderate apply of lace and other trim. She wears a alpine black hat called a capotain over a sheer linen cap and unproblematic jewelry.

- Italian manner: Maria de Medici wears a bodice with split, round hanging sleeves. Her tight undersleeves are characteristic of Spanish influence. From the folds of her skirt, she appears to exist wearing a minor curl over a narrow Castilian farthingale. Note that her oversleeves are the same shape as those worn by Lettice Knollys.

- This portrait (assumed to be Maria de Medici) shows the adaptation of manner to arrange pregnancy. A loose dark gown is worn over a matching bodice and brim, with tight white undersleeves. The lady wears an open figure-of-eight ruff of reticella lace, 1594.

- Italian fashion of the 1590s featured bodices cut below the breasts and terminating in a blunt U-shape at the front waist, worn over open loftier-necked chemises with ruffled collars that frame the head. The Dogaressa of Venice wears a cloth of gold gown and matching cape and a sheer veil over a small-scale cap, 1590s.

- Unknown English lady, formerly chosen Elizabeth I, wears a black gown over a white bodice and sleeves embroidered in black and gold, and a spotted white petticoat. Her hood is draped over her forehead in a way called a bongrace, and she carries a zibellino or flea-fur, with a jeweled face, 1595.

Men'due south fashion [edit]

Overview [edit]

Men's fashionable clothing consisted of a linen shirt with collar or ruff and matching wrist ruffs, which were laundered with starch to be kept stiff and vivid. Over the shirt men wore a doublet with long sleeves sewn or laced in identify. Doublets were stiff, heavy garments, and were ofttimes reinforced with boning.[38] Optionally, a jerkin, commonly sleeveless and oft made of leather, was worn over the doublet. During this fourth dimension the doublet and jerkin became increasingly more colorful and highly decorated.[39] Waistlines dipped 5-shape in front, and were padded to hold their shape. Effectually 1570, this padding was exaggerated into a peascod abdomen.[14] [xix] [twoscore] [41]

Hose, in variety of styles, were worn with a codpiece early on in the menstruation. Trunk hose or round hose were short padded hose. Very curt trunk hose were worn over cannions, fitted hose that ended above the knee. Body hose could be paned or pansied, with strips of fabric (panes) over a total inner layer or lining. Slops or galligaskins were loose hose reaching simply beneath the knee. Slops could as well be pansied. [14] [xix] [42]

Pluderhosen were a Northern European course of pansied slops with a very full inner layer pulled out between the panes and hanging beneath the human knee.[43]

Venetians were semi-fitted hose reaching just below the knee.[42]

Men wore stockings or netherstocks and flat shoes with rounded toes, with slashes early on in the period and ties over the instep afterward. Boots were worn for riding.

Outerwear [edit]

Curt cloaks or capes, ordinarily hip-length, often with sleeves, or a military jacket like a mandilion, were fashionable. Long cloaks were worn in cold and moisture atmospheric condition. Gowns were increasingly former-fashioned, and were worn by older men for warmth indoors and out. In this menses robes began their transition from full general garments to traditional article of clothing of specific occupations, such as scholars (see Academic wearing apparel).

Hairstyles and headgear [edit]

Hair was generally worn short, brushed back from the brow. Longer styles were popular in the 1580s. In the 1590s, young men of style wore a lovelock, a long department of pilus hanging over one shoulder.

Through the 1570s, a soft fabric chapeau with a gathered crown was worn. These derived from the apartment hat of the previous catamenia, and over time the chapeau was stiffened and the crown became taller and far from apartment. Later on, a conical felt hat with a rounded crown called a capotain or copotain became fashionable. These became very tall toward the terminate of century. Hats were decorated with a jewel or feather, and were worn indoors and out.[33]

Close-fitting caps covering the ears and tied under the chin called coifs continued to be worn by children and older men under their hats or alone indoors; men's coifs were usually blackness.

A conical cap of linen with a turned up brim called a nightcap was worn informally indoors; these were often embroidered.[16]

Beards [edit]

Although beards were worn by many men prior to the mid-16th century, it was at this fourth dimension when grooming and styling facial hair gained social significance. These styles would change very frequently, from pointed whiskers to round trims, throughout these few decades. The easiest style men were able to maintain the style of their beards was to apply starch onto their groomed faces. The most popular styles of beards at this fourth dimension include:[44]

- The Cadiz Beard or Cads Bristles, which was named after the Cádiz Expedition in 1596. It resembles a large and discussed growth upon the mentum.

- The Goat Beard resembles a goatee. Information technology is also very like to the 'Pick-a-devant and the Barbula mode of beards.

- The Top was, at the time, a common name for the beard, but information technology referred specifically to a mustache finely clean-cut to a pointed tip.

- The Pencil Beard is a small portion of the beard easing to a point around the eye of the chin.

- The Stiletto Bristles is shaped similarly to the dagger in which information technology obtained its name.

- The Round Beard, just as its name suggests, is trimmed to add emphasis to the roundness of the male cheekbones. Some other common name for this mode was the Bush Beard.

- The Spade Beard derives from the design of a spade which belongs in a deck of playing cards. The bristles is wide on the higher part of the cheeks which then curves at each side to run across at the tip of the chin. This fashion was thought to requite a martial appearance and was favoured by soldiers.

- The Marquisetto; a very sleek trim of the beard in which is cuts close to the mentum.

- The Swallow's Tail Beard is unique in a sense that it entails the groomer to have the hairs from the centre of the chin and separate the hairs toward contrary directions. This is very common variation of the forked bristles, although information technology is greater in length and it is more than noticeably spread apart.

Accessories [edit]

A baldrick or "corse" was a belt commonly worn diagonally across the breast or effectually the waist for property items such swords, daggers, bugles, and horns.[45]

Gloves were often used as a social mediator to recognize the wealthy. Showtime in the second half of the 16th century, many men had trimmed tips off of the fingers of gloves in order for the admirer to see the jewels that were being hidden by the glove.[45]

Late in the period, fashionable young men wore a plain gilded ring, a jewelled earring, or a strand of black silk through 1 pierced ear.[45]

Style gallery 1550s–1560s [edit]

-

i – c. 1550

-

ii – 1557

-

3 – 1560

-

iv – 1560

-

5 – c. 1560

-

6 – 1563

-

7 – 1566

-

8 – 1566

-

9 – 1568

- King Edward Vi of England wears matching blackness doublet, paned hose, and robe trimmed with bands of gold braid or embroidery closed with jewels, c. 1550.

- Antoine de Bourbon wears an embroidered black doublet with worked buttons and a matching robe. His high neckband is worn open at the meridian in the French fashion.

- Don Gabriel de la Cueva wears a jerkin with curt slashed sleeves over a red satin doublet. His velvet hose are fabricated in wide panes over a full lining, 1566.

- Prospero Alessandri wears a astringent black jerkin with the new, shorted bases over a calorie-free grey doublet with rows of parallel cuts betwixt bands of gold complect. His rose-coloured pansied slops are also decorated with cuts and narrow applied gold trim, 1560.

- King Eric Fourteen of Sweden wears a red doublet with golden embroidery and scarlet paned hose in the same fashion. He also wears cerise silk stockings, c. 1560.

- Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk wears a shirt trimmed in blackness on ruff and sleeve ruffles. He wears a belt pouch at his waist. 1563.

- Charles 9 of France wears an embroidered blackness jerkin with long bases or skirts over a white satin doublet and matching padded hose, 1566.

- Highnecked black jerkin fastens with buttons and loops. The detailed stitching on the lining can exist seen. The black-and-white doublet below besides fastens with tiny buttons, German, 1566.

- Portrait of Henry Lee of Ditchley in a black jerkin over a white satin doublet decorated with a pattern of armillary spheres, 1568.

Way gallery 1570s [edit]

-

1 – 1573–74

-

2 – c. 1570

-

3 – c. 1575

-

4 – c. 1576

-

5 – 1577

-

six – 1577

-

7 - 1579

- Henry, Duke of Anjou, the futurity Henry III of French republic and Poland, wears doublet and matching cape with the high collar and figure-of-8 ruff of c. 1573–74.

- An Italian tailor wears a pinked doublet over heavily padded hose. His shirt has a small ruff.

- Sir Christopher Hatton's shirt collar is embroidered with blackwork, 1575.

- French fashion features very short pansied slops over canions and peascode-bellied doublets and jerkins, the Valois Tapestries, c. 1576.

- Sir Martin Frobisher in a peascod-bellied doublet with total sleeves under a buff jerkin with matching hose, 1577.

- Miniature of the Duc d'Alençon shows a deep figure-of-eight ruff in pointed lace (probably reticella). Note the jeweled buttons on his doublet fasten to i side of the front opening, not down the heart, 1577.

- John Smythe wears a pinked white doublet with worked buttons and a apparently linen ruff, 1579.

Way gallery 1580s–1590s [edit]

-

1 – 1582

-

2 – 1585

-

3 – 1586

-

4 – 1588

-

5 – 1588

-

half-dozen – 1588

-

vii – 1590s

-

eight – c. 1590

-

ix – 1580–1600

- King Johan III of Sweden shown in a black doublet with golden embroidery, with matching hose. Black silk stockings, and black shoes with gilt embroidery. He likewise wears a cape in the aforementioned way. He wears a black peak hat with golden embroidery and white feathers. 1582.

- Miniature of Sir Walter Raleigh shows a linen cartwheel ruff with lace (possibly reticella) edging and the stylish small pointed bristles of 1585.

- Sir Henry Unton wears the cartwheel ruff popular in England in the 1580s. His white satin doublet is laced with a red-and-white cord at the cervix. A red cloak with aureate trim is slung fashionably over i shoulder, and he wears a tall blackness hat with a plumage, 1586.

- Unknown man of 1588 wears a lace or cutwork-edged neckband rather than a ruff, with matching sleeve cuffs. He wears a alpine grey hat with a plume which is called capotain.

- Sir Walter Raleigh wears the Queen'southward colors (black and white). His cloak is lined and collared with fur, 1588.

- Robert Sidney wears a loose military jacket chosen a mandilion colley-westonward, or with the sleeves hanging in front and dorsum, 1588.

- Philip Two of Spain (d. 1598) in one-time age. Spanish fashion changed very little from the 1560s to the end of the century.

- Sir Christopher Hatton wears a fur-lined robe with hanging sleeves over a slashed doublet and hose, with the livery collar of the Gild of the Garter, c. 1590.

- Human's cloak of red satin, couched and embroidered with silvery, silverish-gilt and coloured silk threads, trimmed with silvery-golden and silk thread fringe and tassel, and lined with pink linen, 1580–1600 (V&A Museum no. 793–1901)

Footwear [edit]

Elizabeth I'south shoes, 1592

Stylish shoes for men and women were similar, with a apartment i-slice sole and rounded toes. Shoes were fastened with ribbons, laces or merely slipped on. Shoes and boots became narrower, followed the contours of the foot, and covered more of the foot, in some cases upward to the ankle, than they had previously. As in the outset half of the century, shoes were fabricated from soft leather, velvet, or silk. In Espana, Italy, and Germany the slashing of shoes likewise persisted into the latter half of the century. In French republic nevertheless, slashing slowly went out of fashion and coloring the soles of footwear carmine began. Bated from slashing, shoes in this period could exist adorned with all sorts of cord, quilting, and frills.[46] Thick-soled pattens were worn over delicate indoor shoes to protect them from the muck of the streets. A variant on the patten pop in Venice was the chopine – a platform-soled mule that raised the wearer sometimes as high equally two feet off the basis.[47]

Children's fashion [edit]

Toddler boys wore gowns or skirts and doublets until they were breeched.

-

ane – 1551

-

2 – 1555

-

3 – 1556–58

-

four – 1560

-

5 – c. 1570

-

6 – c. 1571

-

7 – 1585

-

8 – 1586

-

ix – 1590

- Francesco de Medici wears an unusual doublet (or robe?) that appears to spike up the dorsum, Italy, 1551

- The sisters of Sofonisba Anguissola wears fashionable dresses suitable for aloof daughters in Italy, 1555

- François Knuckles of Alençon, France, 1556–58

- The French princess Marguerite of Valois wears a white gown with embroidery and pearls. Her hair is twisted and coiled against her head and pinned in place with pearls, 1560.

- Italian children, c. 1570. The girls wearable gowns of striped material trimmed with bands of black, with linen chemises and partlets.

- Infantas Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catalina Micaela of Espana article of clothing miniature versions of adult costume, including gown with hanging sleeves and Spanish farthingales, c. 1571. Their skirts appear to accept tucks to allow them to be let down as the girls abound.

- Two boys at table wear brownish doublets and slops over cannions, the Depression Countries, 1585.

- Catherine van Arckel of Ammerzoden, anile viii, wears a reddish velvet dress with embroidery and several golden bondage. Dutch, 1586.

- A 5-year-old child wears a coif, ruff, and lace-trimmed cuffs, England, 1590

Working grade habiliment [edit]

-

ane – 1565

-

2 – 1567

-

three – 1568

-

iv – 1570

-

5 – c. 1580

-

half dozen – 1594

- German painting of the Concluding Supper in contemporary apparel shows a table servant wearing pluderhosen with total, drooping linings, 1565.

- Dutch vegetable seller wears a black partlet, a front-lacing chocolate-brown gown over a pinkish kirtle with matching sleeves, and a gray apron. Her neckband has a narrow ruffle, and she wears a coif or cap nether a straw hat, 1567.

- Flemish country folk. The woman in the foreground wears a gown with a contrasting lining tucked into her chugalug to display her kirtle. The adult female at the back wears contrasting sleeves with her gown. Both women wearable dark parlets; the V-neck front and pointed dorsum are common in Flemish region. They vesture linen headdresses, probably a single rectangle of cloth pinned into a hood (note knots in the corners backside). Men wear baggy hose, brusque doublets (one with a longer jerkin beneath), and soft, round hats, 1568.

- English language countrywoman wears an open-fronted gown laced over a kirtle and a chemise with narrow ruffs at neck and wrists. A kerchief is pinned into a capelet or collar over her shoulders, and she wears a high-crowned hat over a coif, a chin-cloth, and an apron. She carries gloves in her left hand and a craven in her correct, c. 1555.

- Italian fruit seller wears a forepart-fastening gown with ties or points for attaching sleeves, a green apron, and a chemise with a ruffled neckband. Her uncovered hair is typical of Italian custom, c. 1580. Fruit and vegetable-sellers are often shown with more cleavage exposed than other women, whether reflecting a reality or an iconographic convention is hard to say. It might also reflect the common doubtable in XVI Italia nigh the then-called "treccole", women that sold food of whatever kind in the streets; respectable people tended to run into their going effectually as a sort of cover for prostitution or loose behaviour.

- English gardeners wear cotes with full skirts, hose, hats, and depression shoes, 1594.

Come across besides [edit]

- Blackwork

- Coif

- Doublet

- Elizabethan era

- Farthingale

- Hose

- Jerkin

- Ruff

- Zibellino

Notes [edit]

- ^ Boucher, François: xx,000 Years of Fashion

- ^ Ashelford, Jane: The Art of Dress: Clothing and Club 1500–1914, Abrams, 1996.

- ^ Fernand Braudel, Civilisation and Capitalism, 15th–18th Centuries, Vol one: The Structures of Everyday Life, p. 317, William Collins & Sons, London 1981

- ^ a b c Arnold, Janet: Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd, W Southward Maney and Son Ltd, Leeds 1988. ISBN 0-901286-xx-vi

- ^ Arnold, Janet (2008). Patterns of fashion iv: The cutting and construction of linen shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear and accessories for men and women c.1540-1660. Hollywood, CA: Quite Specific Media Group. p. 10. ISBN978-0896762626.

- ^ Montupet, Janine, and Ghislaine Schoeller: Lace: The Elegant Web, ISBN 0-8109-3553-8

- ^ a b "ELIZABETHAN ERA". www.elizabethan-era.org.uk . Retrieved 2 Nov 2015.

- ^ "Daily Life - Renaissance and Reformation Reference Library | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com . Retrieved two November 2015.

- ^ "Putting on an Elizabethan Outfit". www.elizabethancostume.net . Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ "Re-create of Everyday City Life in London, England During the Renaissance". prezi.com . Retrieved ii November 2015.

- ^ Arnold, Janet (1983). A Visual History of Costume: The 16th Century. New York: Pub Drama Book Publishers. pp. 230–233.

- ^ Norris, Herbert (1997). Daily Life in Ancient Modern London. Online Volume. p. 127.

- ^ Toht, David (2001). "Tudor Custome". Earth History in Context . Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Arnold, Janet: Patterns of Fashion: the cut and construction of dress for men and women 1560–1620, Macmillan 1985. Revised edition 1986. (ISBN 0-89676-083-9)

- ^ Lemire, Beverly; Riello, Giorgio (2008). "Eastward &Westward: Textiles and Fashion in Early Modern Europe" (PDF). Periodical of Social History. 41 (iv): 887–916. doi:10.1353/jsh.0.0019. S2CID 143797589.

- ^ a b c Digby, George Wingfield: Elizabethan Embroidery, Thomas Yoseloff

- ^ Munro, John H. "Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Engineering, and System". In Jenkins (2003), pp. 214–215.

- ^ Boucher, François: xx,000 Years of Fashion, pp. 219 and 244

- ^ a b c Ashelford, Jane: The Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century, 1983 edition (ISBN 0-89676-076-six), 1994 reprint (ISBN 0-7134-6828-9)

- ^ a b c d due east Mikhaila, Ninya; Malcolm-Davies, Jane (2006). The Tudor tailor: Reconstructing 16th-century dress. London: Batsford. p. 20. ISBN978-0713489859.

- ^ a b c d Tortora, Phyllis: A survey of celebrated costume: A history of Western dress, New York: Fairchild Publications, 1994, ISBN 1563670038, pages 164–165.

- ^ Ashelford, Jane (1996). The Art of Dress Clothes and Social club 1500-1915. Great Britain: National Trust Enterprises Express. p. xx. ISBN978-0-8109-6317-seven.

- ^ Kemper, Rachel H: "Costume", 1992, pp. 82

- ^ Arnold, Janet (2008). Patterns of fashion 4: The cut and construction of linen shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear and accessories for men and women c.1540-1660. Hollywood, CA: Quite Specific Media Group. pp. thirteen, fifty–51. ISBN978-0896762626.

- ^ Steele, Valerie (2001). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Printing. pp. 6–12. ISBN978-030009071-0.

- ^ Mikhaila (2006), p. 21.

- ^ Tammie L. Dupuis. "Recreating 16th and 17th Century Clothing". The Renaissance Tailor. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on eight May 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Zeigler, John R. (2013). "Irish mantles, English nationalism: apparel and national identity in early modern English and Irish texts". Periodical for Early on Mod Cultural Studies. thirteen (one): 73–95. doi:10.1353/jem.2013.0001. S2CID 58894238. Retrieved 23 Oct 2015.

- ^ Winkel, Marieke de (i January 2006). Fashion and Fancy: Clothes and Meaning in Rembrandt's Paintings. Amsterdam Academy Press. ISBN9789053569177.

- ^ Zeigler, John R. (2013). "Irish gaelic mantles, English language nationalism: clothes and national identity in early on modern English and Irish gaelic texts". Periodical for Early Mod Cultural Studies. thirteen: 73–95. doi:10.1353/jem.2013.0001. S2CID 58894238. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Sherrill, Tawny: "Fleas, Furs, and Fashions: Zibellini every bit Luxury Accessories of the Renaissance", in Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Book 2, pp. 121–150

- ^ a b Tortora (1994), p. 167

- ^ Köhler, History of Costume

- ^ a b "The Painted Lady-Tudor Portraits at the Ferens". MyLearning . Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "Beauty History: The Elizabethan Era". Cute With Brains. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ The date of 1549 on the portrait of her husband refers to the engagement of his execution, non of the painting, come across notes at Prototype:LadyDacre.jpg

- ^ Vincent, Susan (2009). The Beefcake of Fashion: Dressing the Body from the Renaissance to Today. Berg. p. 49. ISBN9781845207632.

- ^ Ashelford, Jane (1996). The Art of Dress Wearing apparel and Society 1500-1914. Corking Britain: National Trust Enterprises Limited. p. 28. ISBN978-0-8109-6317-7.

- ^ Tortora (1994), p. 157.

- ^ Jones, Stallybrass, Ann Rosalind, Peter (2000). Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Retentiveness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN0-521-78663-0.

- ^ a b Tortora (1994), pp. 158160.

- ^ Arnold, Patterns of Fashion...1560–1620, pp. 16–eighteen.

- ^ Cunnington, C. Willett; Phillis Cunnington; Charles Beard (1960). A Lexicon of English Costume. London: Adam & Charles Black LTD.

- ^ a b c Cunnington, C. Willett; Phillis Cunnington and Charles Beard (1960). A Dictionary of English language Costume. London: Adam & Charles Blackness.

- ^ Kohler, Carl (1963). A History of Costume. New York, NY: Dover Publications. pp. 227–274.

- ^ "Elizabethan Shoes".

References [edit]

- Arnold, Janet: Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd, West South Maney and Son Ltd, Leeds 1988. ISBN 0-901286-20-vi

- Arnold, Janet: Patterns of Fashion: the cut and structure of clothes for men and women 1560–1620, Macmillan 1985. Revised edition 1986. (ISBN 0-89676-083-9)

- Arnold, Janet: Patterns of fashion 4: The cut and construction of linen shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear and accessories for men and women c.1540-1660. Hollywood, CA: Quite Specific Media Group, 2008, ISBN 0896762629.

- Ashelford, Jane: The Art of Wearing apparel: Vesture and Society 1500–1914, Abrams, 1996. ISBN 0-8109-6317-5

- Ashelford, Jane. The Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century. 1983 edition (ISBN 0-89676-076-6), 1994 reprint (ISBN 0-7134-6828-9).

- Boucher, François: xx,000 Years of Fashion, Harry Abrams, 1966.

- Digby, George Wingfield. Elizabethan Embroidery. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1964.

- Hearn, Karen, ed. Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530–1630. New York: Rizzoli, 1995. ISBN 0-8478-1940-Ten.

- Jenkins, David, ed. The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-52134-107-3.

- Kõhler, Carl: A History of Costume, Dover Publications reprint, 1963, from 1928 Harrap translation from the German language, ISBN 0-486-21030-8

- Kybalová, Ludmila, Olga Herbenová, and Milena Lamarová: Pictorial Encyclopedia of Fashion, translated by Claudia Rosoux, Paul Hamlyn/Crown, 1968, ISBN 1-199-57117-ii

- Mikhaila, Ninya, and Malcolm-Davies, Jane: The Tudor tailor: Reconstructing 16th-century dress. London: Batsford, 2006, ISBN 0713489855.

- Montupet, Janine, and Ghislaine Schoeller: Lace: The Elegant Spider web, ISBN 0-8109-3553-eight

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Wear and Textiles, Volume 2, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press, 2006, ISBN ane-84383-203-8

- Scarisbrick, Diana, Tudor and Jacobean Jewellery, London, Tate Publishing, 1995, ISBN 1-85437-158-4

- Steele, Valerie: The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale Academy Press, 2001, ISBN 030009071-4.

- Tortora, Phyllis: A survey of celebrated costume: A history of Western dress. New York, Fairchild Publications, 1994, ISBN 1563670038.

External links [edit]

- The Elizabethan Costuming Page

- Description Of Elizabethan England, 1577(from Holinshed'south Chronicles), Chapter Vii: Of Our Dress And Attire

- Fathingales and Bumrolls

0 Response to "Women's Fashion in Mid 1500s Germany"

Post a Comment