Pic Fashion in the Cold War

A painter introduced ane of the Cold War'southward most enduring, powerful, and pop metaphors: the Iron Mantle. Winston Churchill—a passionate and prolific amateur painter in addition to his role as British prime government minister and international statesman—invoked the term in 1946, in a spoken language given in Missouri, with American president Harry Truman in attendance:

…an iron curtain has descended across the continent. Behind that line prevarication all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. … [A]ll are subject, in one form or another, non simply to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in many cases, increasing measure out of control from Moscow.

Churchill'south Iron Curtain provided a bright image of a fiercely divided Europe subsequently Globe State of war II. To the e, in countries like Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and what was shortly to go East Germany, the Soviets imposed communist dominion. And in the Western half of Europe, the nations of France, Great Britain, Italy, and the future Due west Federal republic of germany aligned themselves with the United States and at least the basics of its backer economical system. For more than twoscore years, Churchill's provocative image defined the Cold War's binary logic, fifty-fifty encompassing the world across Europe, save for those nations that attempted to remain neutral. In the popular imagination, people and goods passed through the bulwark only with great difficulty. It is not hard to imagine how Churchill's Atomic number 26 Pall became conflated with the Berlin Wall when it was erected in 1961. Metaphor became reality.

While the global situation was more than complicated, this binary conception of the globe nevertheless wielded significant historical consequences. The Cold War is the key story of the 2nd half of the twentieth century—essential for explaining what happened effectually the earth and why. Even disputes that, at their start, had little or nothing to practice with the Cold War, morphed into of import battlegrounds for the conflict. Merely what was the Common cold War? Put very only, it was the ideological boxing between the United States and the Soviet Union (and their respective allies) that started at the end of Globe War Ii in 1945 and ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Bloc.

While both nations had fought together in World War 2 to defeat Nazi Deutschland, each rushed in to fill the vacuum left by Hitler'due south defeat and the resulting political upheaval, and did so with their own interests in mind. Who would control the reconstruction of postwar Europe? Would it be rebuilt to reverberate American-style democratic capitalism or Soviet-style socialism? These questions lay at the heart of the Common cold War'south origins, and they also carried great consequences beyond the continent, as Japan's defeat in World War II left its own void in Asia, and Western powers became unable or unwilling to maintain their hold on colonies or client states in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. In the optics of the ii superpowers, other nations—whether new or old—needed to choose sides in the Cold War.

The conflict intensified by 1948 and remained fierce until its end, though a period in the 1970s, known as détente, saw the renewal of diplomatic relations and the signing of agreements betwixt Common cold War adversaries. Fifty-fifty a brusque list of major events of the Cold War tin bring back a sense of the period's anxiety and tension: the Korean State of war in the early 1950s; Soviet invasions to quell autonomous protests in East Berlin (1953), Budapest (1956), and Prague (1968); the failed CIA-orchestrated invasion of Cuba known equally the Bay of Pigs in 1961; successful CIA-backed regime changes in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), Congo (1960), also as at least palliating others such equally Brazil (1964) and Chile (1973); the Cuban Missile Crunch in 1962; the Vietnam War, which dominated the mid- to late 1960s, as well equally other postcolonial conflicts subsumed by the Cold State of war; and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. Looming over all these events, likewise equally more than "minor" ones, was the threat of nuclear apocalypse. Past 1949 both sides had the Bomb, and by the mid-1960s possessed sufficient weaponry to end the world many times over. Thus even small flare-ups evoked existential questions of life and death on the scale of the human species itself.

The Polish anti-authoritarian movement Orange Culling made this graffiti dwarf a revolutionary symbol. Photo by Tomasz Sikorski.

The Cold War pitted two and then-called "master narratives" against each other. Did capitalism, with its discourses of private holding and private choice, represent the highest form of human organization? Or was communism—which had denounced course-based hierarchies and the profit motive—the more evolved philosophy? Capitalism and communism take mutual roots. Both are products of Western modernization, and both rely on utopian notions: The former promises private choice and the possibility that anybody can get wealthy, and the latter claims as its goals—equality, meaningful labor, and commonage life without greed. In this sense, the Cold War was waged over the pregnant of "progress," and was every bit much a semantic battle over language and the estimation of the globe, equally it was a political–military machine struggle. And when, by the end of the 1960s, the illusions of both utopian visions seemed to be violated, whether by Soviet tanks in the streets of Prague, or American bombs in Vietnam, the very terms of the Common cold State of war's beingness came nether interrogation. The disharmonize'southward empty rhetoric and false oppositions—abundantly clear past the cease of 1968—encouraged advanced thinkers, such equally Jacques Derrida, to suggest the relativity of all ideologies and the illusionary nature of binaries. Put simply, the Cold War helped spur postmodernism, as the art of the 1970s and beyond demonstrates.

As the Cold State of war progressed, countries well beyond Europe were forced to engage, wittingly or unwittingly, with this binary imposed past the two global superpowers. Some chose sides based on ideology or more than practical concerns such as the hope of economic assist; others had the decision fabricated for them, whether through military machine action from exterior or through internal coups secretly engineered by American or Soviet officials. Countries that attempted to remain neutral often found themselves fatigued into Common cold War political battles despite their best efforts. The doctrine of containment, formulated by the American diplomat George Kennan at the starting time of the Cold State of war, reiterated Churchill's Iron Mantle metaphor. Sending a long cablevision from Moscow in 1946, Kennan advocated preventing further Soviet territorial and ideological advances through containment: Communism, not unlike a affliction, could be controlled by quarantine. This idea loosely guided American foreign policy for the length of the conflict. With its connotations of strict demarcation, the term became a metaphor for the Cold War more broadly—a world divided into two singled-out camps with no overlap.

The Cold War'due south binary rhetoric failed, nevertheless, to describe reality accurately: Local situations demanded more nuanced and specific understandings. For example, in the Vietnam State of war, many soldiers in the communist north were fighting for national independence and self decision, not for the ideological reasons ordinarily ascribed to the conflict. Initially, the Vietnamese communist leader Ho Chi Minh even looked to the U.s.a. as a model for its own anti-colonial revolution, identifying Americans equally the "guardians and champions of earth justice" in a letter of the alphabet to President Harry Truman in 1946. Such anti-colonial sentiments, not Cold State of war beliefs, too fueled many Afghan "freedom fighters" in their state of war against the Soviets in the 1980s. Many of these anti-Soviet soldiers shortly too became anti-American. In 1988, some of them founded Al-Qaeda, the main enemy of the United states of america in the years before and post-obit the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001—thus confirming divergent reasons for wanting the Soviet presence out of Afghanistan. The Cold War was thus a way of seeing the world. This ideological lens transformed circuitous constellations of global and local events into a manageable framework: Soviet communism versus American commercialism. The visual qualities suggested by the phrase "ideological blindness"—a phrase that came into pop utilise at the very commencement of the Cold War, describing how rigid political beliefs can twist perception and interpretation in irrational ways—leads to a consideration of the importance of images, specifically art, to the conflict.

The British Pop artist Gerald Laing addressed the very effect of ideological blindness in an of import painting from late 1962 entitled Gift (of the Cuban Missile Crunch Oct 16–28 1962), featuring both protagonists of the global showdown over the presence of Soviet missiles in Republic of cuba: John Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. Because the work is painted on angled vertical slats, viewers encounter an image of Kennedy and an American flag when they are to its correct, but from its left they run across Khrushchev in front of the Soviet standard. Both representations take the grade of simplified political propaganda, more reminiscent of caricatures than advisedly studied portraits. In add-on to mapping Cold State of war sides onto physical space, determined past the viewer's position in the gallery, Souvenir dramatizes how viewers can interpret the same painting in radically different means: Once one understands how the painting works, one can choose to run into Kennedy or Khrushchev.

Withal, we should also consider the result of the painting when viewed straight-on, which is how most people typically approach a work hanging on a wall. From this perspective, the painting is literally pulled in two ideological directions, resulting in a jumbled mess—well-nigh like a period television flickering betwixt two stations. The painting suggests that the fiercely partisan view imposed by the Cold War is not a natural manner to regard the world; individuals have to expect at the painting askance—stepping away from a more natural practise of one's vision—to see an uncomplicated representation of the leaders of capitalism and communism. The painting'due south key view better represents the everyday experience of the Common cold War, especially in countries other than the Soviet Union and the United States: a resistance to aligning oneself rigidly on either side of the conflict. Between the two poles, reality was contentious and scrambled. In 1957, just a few years before Laing painted his canvas, the French filmmaker Chris Mark fabricated a similar point in his documentary Letter from Siberia when he repeated footage of route workers in a Siberian city three times, each with a different vox-over: one from a staunchly Soviet perspective, i from an American one, and the third straddled betwixt the two. Marker's flick exposes the way that even "objective" imagery—whether in photographs or films—can be twisted by narration or captions.

Ane of the 20th century'southward most consequential photographs can assist clarify the stakes of Laing's painting in terms of its relation to the Cuban Missile Crisis, as referenced in its championship. At first glance, the high-distance photograph—featuring a landscape with fields, trees, and roads—does not seem peculiarly interesting, at least non without captions to explain or contextualize information technology. This photograph, however—taken by an American U-ii spy plane high higher up communist Republic of cuba on Oct xiv, 1962—proved to be a crucial slice of prove. Analysts at the National Photographic Interpretation Center in Washington, examining miles of photo transparencies with visual aids, constitute important needles in a giant intelligence haystack: the subtle visual signatures of offensive Soviet missile systems. This photograph helped establish that the Soviets were secretly installing nuclear weapons in Cuba.

Usa government officials needed this image to exist perceived every bit a truthful document across the earth, and soon fabricated it, every bit well as other similar photos, public. But the picture itself, especially when stripped of the captions supplied by professional person interpreters, proves zilch to untrained eyes. When first shown this image and others at the White Business firm, President Kennedy suggested that one of the sites in question looked like a "football field," not a missile site. A high-ranking CIA official even admitted that whatsoever non-specialist would accept to accept it "on faith" that the epitome showed what its captions said information technology did. So while this picture helped evidence to the world (and the Un) the beingness of offensive missiles in Cuba, it is shocking that this well-nigh abstract photograph—and other similar examples—were never seriously questioned publicly. The perceived certainty of the image'southward captions suppressed its pictorial ambiguity.

Cildo Meireles, Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca Cola Project (1970).

In the early years of the Common cold War, the fine art historian E.H. Gombrich remarked that what viewers bring to an paradigm—including their visual training and political ideology—helps dictate how that image is interpreted. Gombrich called this automatic "completion" by the viewer, "the beholder's share." In terms of the Cold State of war, a Soviet viewer would more probable be skeptical about the validity of images taken over Cuba than an American would, for example. Ideology had e'er guided the estimation of images, just mayhap never yet on the Cold State of war's systematic, global scale. While an extreme case, this aerial surveillance photo highlights not only a missile crisis but too a broader epitome crisis in the Cold War. Important examples were not only cryptic, but were likewise interpreted through ideological filters as "fact."

When discussing art, Winston Churchill seems to have understood the fluid nature of images. While certainly not an avant-garde painter, he viewed painting as an activeness where the quirks and ambiguities of vision could be explored. He addresses this notion in "Painting as a Pastime," an essay from the early 1920s, published as a stand-lone book soon subsequently his Iron Curtain speech. In a remarkable passage that Gombrich also discussed in his volume Art and Illusion (1960), Churchill describes painting in conspiratorial terms:

The canvas receives a message dispatched ordinarily a few seconds before from the natural object. Merely information technology has come up through a post office en road. It has been transmitted in code. It has been turned from low-cal into paint. It reaches the canvas [as] a cryptogram. Not until it has been placed in its right relation to everything else that is on the canvas tin information technology be deciphered, is its pregnant apparent, is information technology translated once once more from mere

pigment into light.

If Churchill'south view of the geopolitical world was leap by the absolute nature of the emerging Cold State of war binary, then his understanding of painting was decidedly more nuanced. His painter is sure neither most representation nor the stability of the visual globe; instead he or she resembles a spy who waits for enigmatic messages to go far, decodes these "cryptograms," so translates them into a specific language of painting. A consideration of Churchill'due south words on painting, in tandem with his "Iron Curtain" voice communication, reveals a complex fluidity lurking simply beneath his image of a simple binary world. And by theorizing the medium via a language of epitome transmission (images are "dispatched" and "come through a mail role") he relates painting to other image cultures that were used propagandistically on both sides during the Common cold State of war: press photographs, television screens, and satellite images. Images—even those that are presented as stable and factual—can exist flexible, contradictory, and changeable. Or to use the popular language of the Cold State of war, images—including works of art—can be spies that hide secrets in plain sight. It may exist no coincidence that one of the most infamous Soviet spies in this menstruation was the renowned British fine art historian and Queen'south curator Anthony Blunt. Blunt'south activities included serving as the courier for a key Soviet asset inside the British secret service, and probably alerting Great britain's nigh notorious double agent of the period, Kim Philby, of his imminent abort, allowing Philby to escape to Moscow from Beirut. Edgeless's understanding of the mutability of images—how paintings tin house and manage contradictions, ideological and otherwise—might have provided a model of charade that allowed him to work undetected for years.

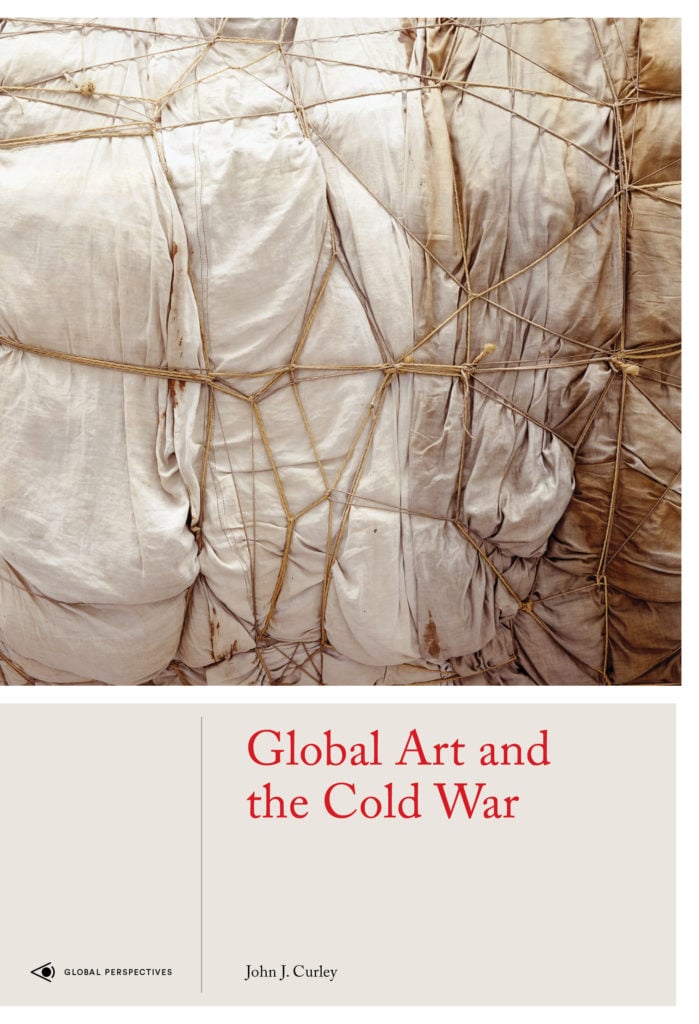

The embrace of Global Art and the Cold War by by John J. Curley.

Despite the apparent certainty of Churchill's anti-communist political position—which divided the world between accented good and accented evil—his theory of art works against such binary conviction. And nonetheless Churchill's apparent contradiction was consistent with the performance of the conflict. Common cold War factions required certainty in their messages, and yet such clarity, whether visual or ideological, was incommunicable to achieve.

Some thinkers from the period understood the conflict in such a fashion—every bit one fought at the level of representation. As media theorist Marshall McLuhan wrote in 1964, the Cold War was "really an electrical battle of data and images." Because there were no direct, sustained military confrontations between the U.s.a. and the Soviets (other than proxy wars like Vietnam and Transitional islamic state of afghanistan), the disharmonize was largely waged on the level of intelligence gathering and media representations—propagandistic efforts from both sides to convince the world, and possibly themselves, of the definiteness and historical inevitability of their corresponding paths. Even nuclear deterrence was predicated on conveying a credible image of nuclear strength and was not necessarily dependent on the actual number of weapons. And things were rarely what they seemed in this battle of images, as Common cold War historian John Lewis Gaddis suggested when he compared the disharmonize to a theater in which "distinctions between illusions and reality were not ever obvious." Pioneering Cold War art historian Serge Guilbaut recently agreed with such an cess, comparison the conflict to an "almost Hollywood super-production." While some fine art objects served ideological ends, many works of art from the period pulled back the Iron Curtain to expose the limits and dangers of the Cold War's superficial and overly simple binaries.

Excerpted fromGlobal Fine art and the Cold Warby John J. Curley. Copyright © 2019 by John J. Curley. Excerpted by permission of Laurence Rex Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. No office of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Desire to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that bulldoze the chat forward.

0 Response to "Pic Fashion in the Cold War"

Post a Comment